by Dr. Russell Keck, associate professor of English

Several years ago, I committed myself to reading at least one Faulkner novel per summer until I had completed his entire oeuvre. I got this idea from my colleague Michael Claxton who had undertaken the same task but with Charles Dickens. As a scholar of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, my usual literary encounters are with the likes of Chaucer, Shakespeare, Lanyer, Donne and Milton — that is, very British and very old. Being a modern author who is decidedly American — or, more accurately, unabashedly Southern — Faulkner stands out among the crowd in both substance and style. Yet, as one who was raised in Arkansas and now works and lives next door to the Mississippi Delta, I find Faulkner’s works more than masterpieces worthy of deep reading and thoughtful reflection; they are, of a sort, artistic heirlooms, partaking in a shared memory and drawn from collective past with which I am intimately familiar. At this point, opening up a Faulkner novel each summer feels like going to a family reunion, in which I learn a little more each year about the relationships and rivalries that have defined these newfound relatives of mine.

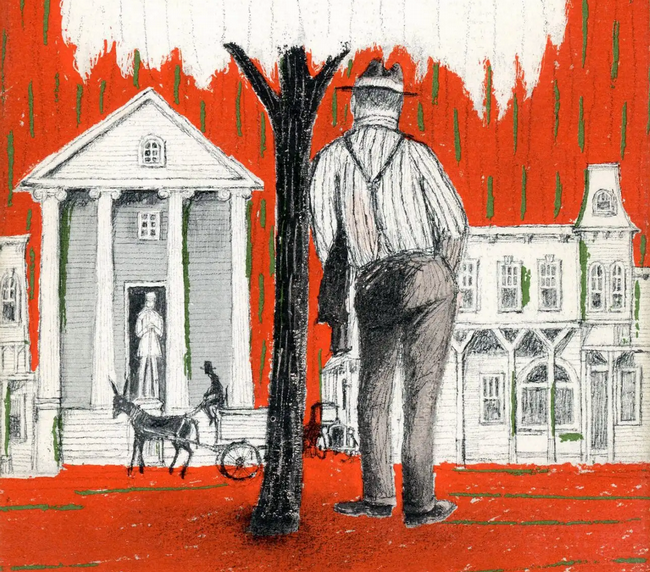

My recent selections have come from Faulkner’s Snopes trilogy, a series of novels focused on the social ascension of Flem Snopes. It is Flem’s Odyssean machinations and Mephistophelian deal-making which lift him, and his ever-growing number of family members, from poor tenant farmers to store owners, schoolmaster, bankers, civic officials and politicians. Flem’s rise occurs much to the chagrin of the other residents of Yoknapatawpha County (the fictional setting of most of Faulkner’s works). This summer I am making my way through the second work of this trilogy, The Town, which takes place in the county seat of Jefferson.

The challenge with Faulkner novels, written in his (in)famous stream of consciousness style, is that they take time. But that is precisely how readers can best appreciate them. Characters have their own way of talking and thinking, and actions are nearly always conveyed through recollections, anecdotes and memories integrated into conversations either between characters or between the reader and narrator (which switches among the main characters each chapter). Details of events can be sparse and understated, while the mental and emotional processing of said events can be meandering and overstated. This artistic choice is one I have come to deeply admire, for what I think Faulkner does with his storytelling is invite us into the very minds of his characters. When we come to understand them, their idiosyncrasies, their vices and virtues, their ways of being, we experience not just a story but a sense of living out their lives in real time.

The main characters of The Town are:

Their lives initially revolve around Gavin’s heated feud with Jefferson’s mayor, Manfred de Spain, for the attention of Eula Snopes, Flem’s beautiful but unfaithful wife. The novel then turns to Gavin and Ratliff’s attempts at circumventing Flem. They learn too late that he is always two-steps ahead of any potential resistance and come to understand that he seeks complete sociopolitical domination. Time and again, Flem outwits Jefferson’s old guard. Gavin rails against Flem’s expanding power, describing his opportunistic presence as a parasite on the town. Flem uses every new position, from superintendent of the local power plant to vice president of the Bank of Jefferson, as a rung upon which to win influence, gain favors (or material for blackmail) and build wealth, though Flem makes sure his stratagems are never directly traceable to him. What’s more, each time he vacates a position, he places a new family member in his stead. However, should another Snopes impede his progress either by idiocy or goodwill, Flem has no compunction turning on his own.

Faulkner’s The Town offers gripping world building, richly varied and unique characters, and narrative action that would be the envy of raconteurs and professional gossips alike. It is also a remarkable study on the effects of seeking power. I can’t help but feel beneath the text the spiritual current of Matthew 16:26 — “For what will it profit them if they gain the whole world but forfeit their life?”

Like the ending of all second works in trilogies, the conclusion of Faulkner’s The Town is one filled with sorrow and defeat — but with a small glimmer of hope mixed in. I daresay the final third of this novel is presented as a kind of classical tragedy.

Linda Snopes graduates high school and waits for her father, Flem Snopes, to allow her to attend university. When she does, Linda will be free of Flem’s growing dominion, especially if she decides to marry, which is sure to happen given the beauty she has inherited from her mother. With her will go a controlling portion of stock in the Bank of Jefferson, which Flem wants all to himself as his seat of power

Feeling that his time is running out to secure what Ratliff defines as the ultimate pursuit of “respectability,” Flem launches a cruel offensive — including ruined reputations and blatant blackmail — to coerce Linda and Eula to sign over their shares. The ensuing drama centers on Flem’s personal cursus honorum to become the de facto ruler of Jefferson and, by extension, Yoknapatawpha County.

I am struck by two aspects of this concluding section of The Town. The first is that the community of Jefferson becomes its own character. Faulkner imbues this community with moral complexity that rivals the individual characters in the narrative. The community is aware of a long-standing affair but doesn’t condemn it until Flem forces them to confront it head on. But the sin is their own because none before had reported it or called it into account. Why? Because they admired the devotion of these illicit loves, faithful to each other in their unfaithfulness to marriage vows. They also found entertainment in the gambits and maneuvers of all the parties involved in this notorious affair. Lastly, the town began to resent Flem’s tightening grip on their livelihoods. If the climax is in the vein of a classical tragedy, then the town certainly takes up the mantle of a chorus (with the three narrators as its representatives), commenting and reflecting on the tragic circumstances that affect them all..

The second aspect is Faulkner’s language, particularly the voice of Gavin who manages to describe with such astonishing threads of consciousness — simultaneously free-flowing and fragmented, reflective and repetitive, sonorous and stultifyng—the pain of inevitability, of loss, and of the struggle holding onto hope that I was convinced Faulkner had found a way to record the inner voice of the human mind. Faulkner’s language seems to capture the moments of thought just as they are forming the very words, phrases and sentences they tell themselves or others. At times his language becomes sublime. Here’s an example, “Then, as though, at signal, the fireflies—the lightning-bugs of the Mississippi child’s vernacular—myriad and frenetic, random and frantic, pulsing; not questing, not quirking, but choiring as if they were tiny incessant appeaseless voices, cries, words. And you stand suzerain and solitary above the whole sum of your life beneath that incessant ephemeral spangling.” I cannot imagine a better way to describe the sense of taking in a summer evening.

Having finished two novels in the Snopes series, I feel like I have spent several lifetimes in Yoknapatawpha County, but that is one of the exhilarating benefits of reading such books. Faulkner offers us all the complexities and marvels of life through his flawed characters, mimetic setting and captivating narratives in a language that reflects our own raw and wondrus ways of thinking. I cannot wait to return to Jefferson next summer and catch up with Gavin, Ratliff, and Chick and find out what has become of Flem, Linda and the rest of the Snopes family.